Who Owns Growth? (And Why Analytics Pays the Price) - Issue 301

Why marketing and product see different realities, and how analysts bridge them without breaking trust.

Welcome to a subscriber-only issue of my Data Analytics Journal, where I write about data science and analytics.

Analytics is mainly a supporting function. We serve everyone - finance, product, marketing, PR, and HR, and depending on who we support, that often defines the type of analyst we become (see Which Analyst Are You?).

One of the most demanding and common areas for analytics to support is growth.

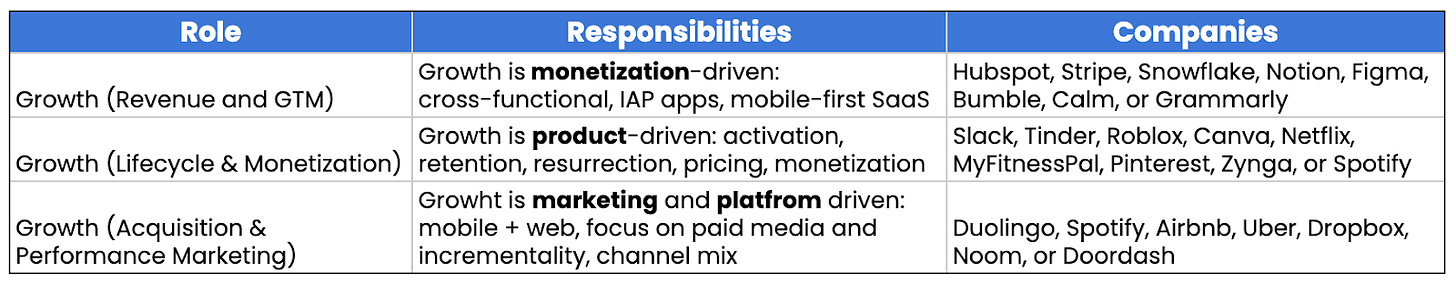

Some teams call it growth marketing. Others mean product (or product-led) growth. Some use “growth” to mean monetization. There’s no single, unified definition of what growth includes, and it looks very different from company to company:

On paper, these growth roles can sound similar. In practice, they translate into very different strategies, projects, and day-to-day work for the analyst supporting them.

In this publication, I’ll vent about how hard it can be to support growth leaders with very different backgrounds, and how differently we can interpret the same “growth” project. I’ll also share what I’ve learned about serving each type of growth leader well, and how to navigate between very different flavors of growth.

Marketing analytics vs. product analytics

There is significant overlap between product and marketing analytics. Most of us have roughly the same skills and understand each other’s context and domain specifics well. Very often, analysts do both, especially in SaaS and early-stage companies.

Marketing analytics: modeled, not measured

I’ve often been lucky. By choice, I usually don’t take pure marketing analytics projects. I try to stay away from ROAS reporting and ad performance dashboards. Not because marketing analytics is less exciting, but it’s because I don’t trust most marketing tools enough to ground strategy on them. And setting your profitability on some conversion that the vendor sends you, and which you can’t replicate, is so out of my comfort zone ☠️.

And here is more:

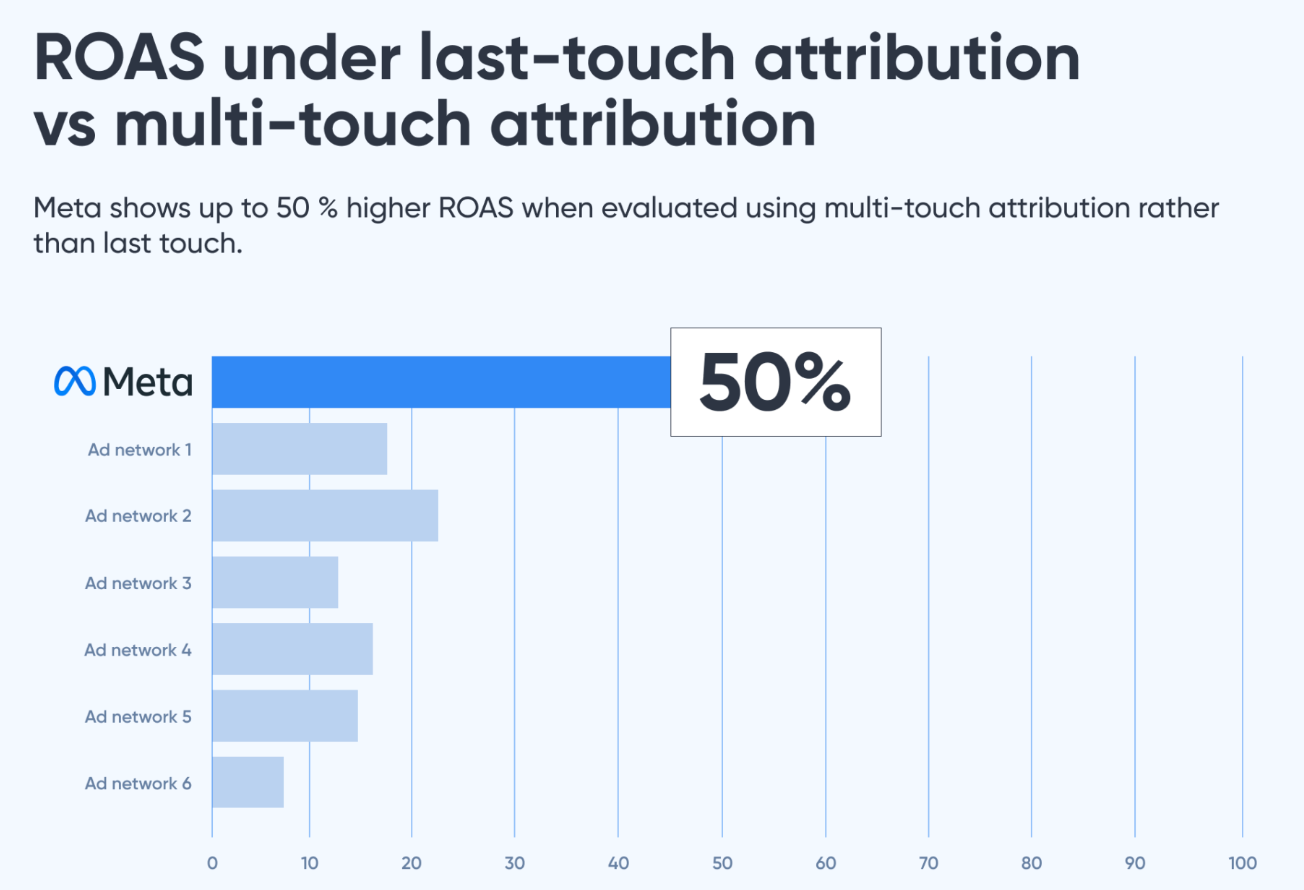

Platform self-attribution bias, where apps and channels optimize to prove their own value.

Limited transparency into modeling and attribution logic. Wild west there.

Heavy dependence on probabilistic matching and modeled conversions. Replicating that modeling is another story.

Post-privacy changes (SKAN, ATT), signal loss is real and often undercommunicated.

Incrementality is rarely measured properly, and most teams still read correlation as causation.

Easy to optimize for cheap conversions instead of valuable users.

And more. No offense to my marketing analytics peers (I genuinely feel for all of you), but a lot of this ecosystem feels like: “It might be a signal… so let’s all pretend it works.” In many cases, teams are optimizing against estimates that can’t be independently validated or replicated.

Product analytics: measured user behavior

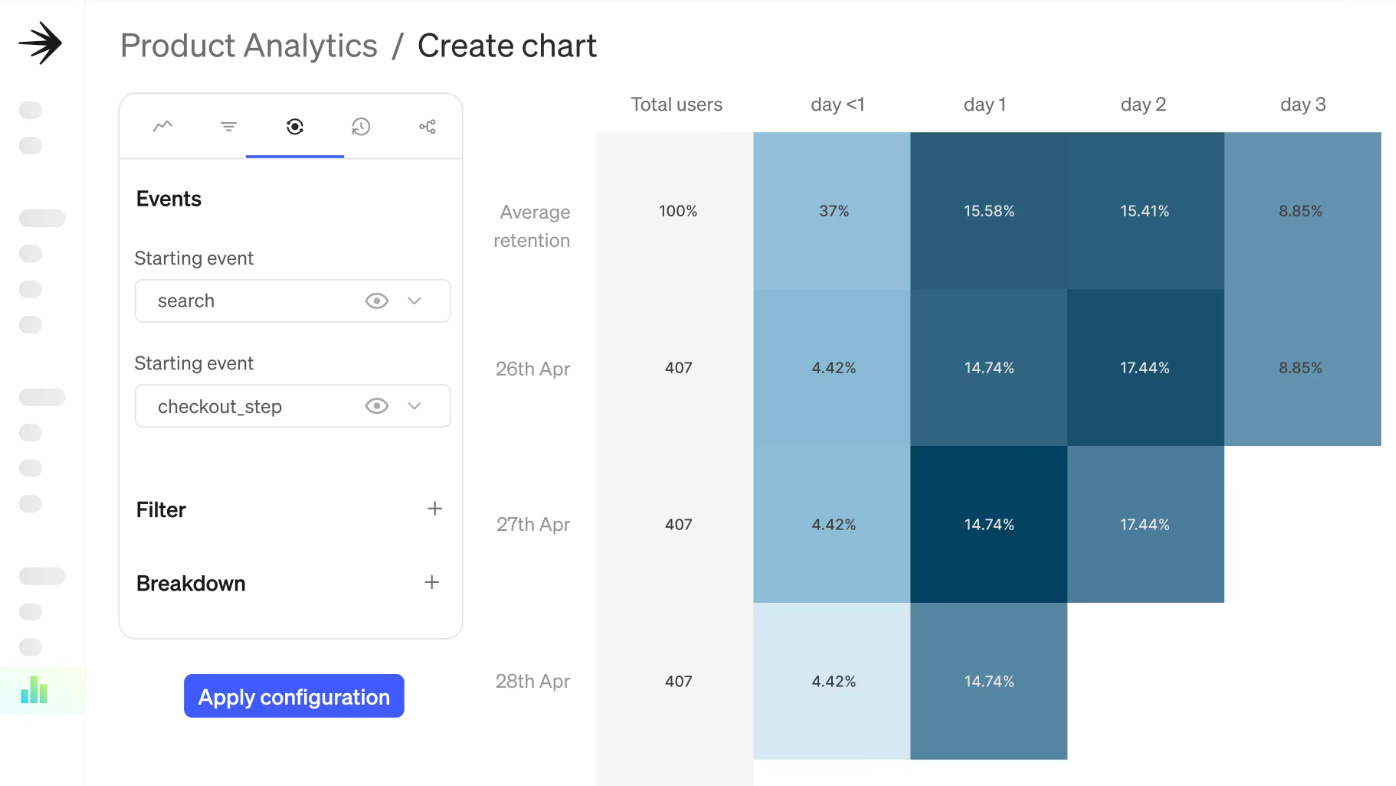

Product analytics is different. Unlike marketing, finance, or business analytics, it’s grounded in the product itself. Product analysts are immersed in how the product works - what users do, what they struggle with, and what drives outcomes.

But the best part is the data. Most of what we use comes straight from our own platforms and devices. It’s first-party and instrumented in-house. You can usually reproduce the same metric multiple ways, using different event logic, calculation methods, or even different sources, because the raw building blocks are observable. Everything ties back to a user_id, often a session_id, and a trail of events and transactions you can count, compute, and model. That’s a different level of data truth, and it opens the door to a wide range of projects (see Inside Product Analytics: Decoding User Behavior).

And it’s completely normal for product and marketing teams to disagree on “the same” metric. They’re often measuring different things from different angles: measured behavior vs. modeled attribution, user-driven vs. channel-driven, in-product reality vs. platform-reported outcomes.

So everything is great until you join a team where marketing drives growth, monetization, and product. Which is often the case for smaller apps and products.

Let me step back.