SaaS Metrics Reporting: A Peek Behind The Curtain - Issue 112

Monitoring and reporting of SaaS health. Challenges and caveats.

Hello and welcome to my Data Analytics Journal newsletter, where I write about data analysis and data science.

If you’re not a paid subscriber, here’s what you missed this month:

Why You Shouldn’t Stop A/B Tests Early - covers the most asked questions on experimentation in analytics: how long should I run an A/B test? Why is it recommended for 2 weeks? How do I stop the test early? Why are slow (phased) rollouts dangerous? And more.

How To Pick The Right Chart - recommendations and guides on how to appropriately choose the right visualization for your analysis.

Top Data Trends That Will Shape The Upcoming Years - what are the future data trends across ML and AI, and how do we prepare now to accelerate business growth, data team productivity, and efficiency?

I am in Austin, Texas this week and thought it might be a good time to touch on analytics reporting. Today’s topic is dear to anyone who is on a mission to monitor SaaS metrics and KPIs and report growth to their board, investors, executives, or whoever you happen to owe your soul to. I’ll walk you behind the curtain of reporting to illustrate how both easy and challenging it can be to create a true story of the business's health and growth.

Caveat: below I’ll dig down into common SaaS metrics, so you have to be familiar with most SaaS KPIs and their relationships to follow the article. If you are a beginner or getting started with SaaS analytics, please refer first to The SaaS Metrics Cheat Sheet from ChartMogul or this nice roundup of 15 Metrics Every SaaS Company Should Care About from Hubspot.

As someone heavily involved in SaaS health monitoring and reporting for many years, let me assure you that the Board always asks for these 5 preferred KPIs:

ARR/MRR

ARPU

CAC

LTV

Churn

Of course, you have to provide data on many additional metrics including Net New Everything, ASP, ACV, expansion revenue, retention, NPS, and much more.

And (obviously) investors expect KPIs in a table view including MoM and YoY stats, and broken down by regions. And, of course, cohorted! Nothing today is reported un-cohorted. We passed that stage back in 2003 when the second movie of Harry Potter was released and search engine marketing (SEM) became a thing. Today it’s expected that retention, LTV, and churn should be cohorted. I believe that less than 20% of companies actually can report cohorts cleanly, but who cares about the details like missing data, wrong data, or low precision and lack of trust? I do. I care. That’s why I created this publication.

KPIs to be cautious with

All KPIs mentioned above (except ARR and MRR, which are more straightforward) open an ocean of opportunities for analysis to deviate and mislead (and not necessarily on purpose). For example:

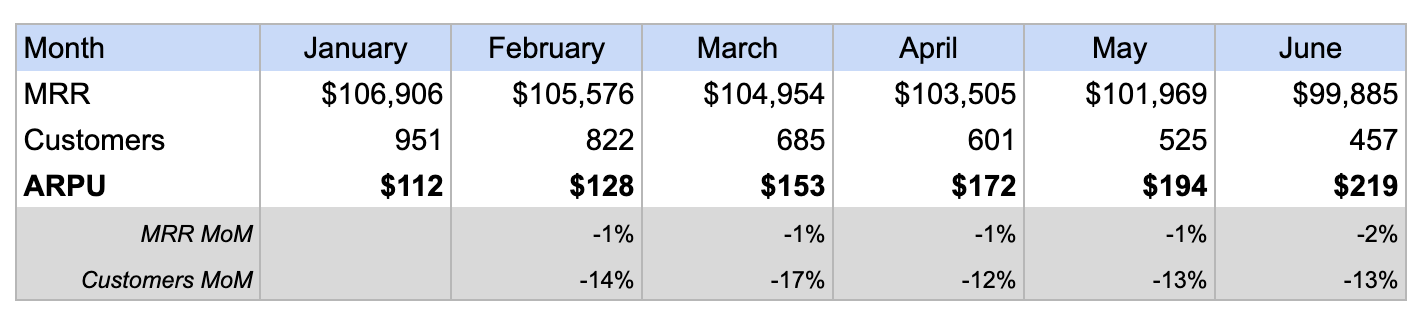

ARPU

ARPU can be a vanity metric or outright misleading. Contrary to its purpose, it will rise when you are losing customers. It’s just simple math:

Over 6 months, with MRR and the number of customers declining, ARPU shows a 95% increase. Let’s celebrate!

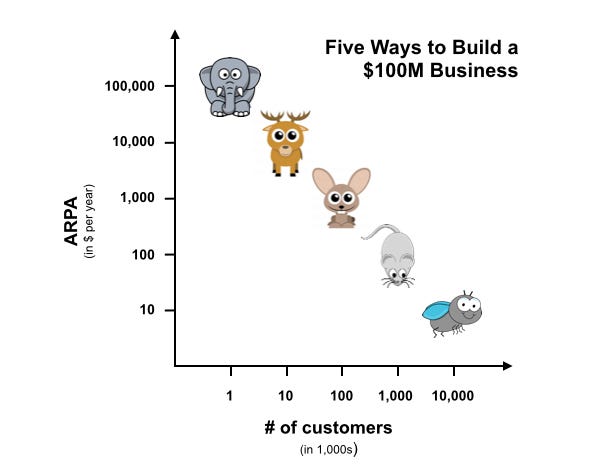

And, like any average, it can betray the true health of the business. If not correctly used, blended ARPU (which is often used when a small segment of your customers accounts for a large part of your revenue) can effortlessly promote you from a fly to a mouse. Bye-bye, dear little fly!

Christoph Janz Five ways to build a $100 million business and Five years later: Five ways to build a $100 million SaaS business

To be fair, following Christoph’s logic, no amount of ARPU calculation error will get you from a rabbit to a deer or a higher bucket on a quest to reach 100M ARR. So his ARPU segmentation makes complete sense. But for the “consumer-focused” business reporting (with ARPU $100 or less), it’s possible to screw up and fool that chart.

Analytics can get messy, but if any KPI becomes green when you lose a customer or revenue, that’s not a good KPI to follow :) At some point I will dedicate a publication to ARPU - why it’s tricky, and in many cases quite frankly useless in monitoring growth.

CAC and LTV

Why these SaaS KPIs are challenging:

CAC is a dark world, full of mystery.

LTV segmentation per marketing channel often isn’t trustworthy.

Gross profit data (promos, discounts, refunds) are not easy to get.

Any LTV has to be maintained and tweaked.

Here is the thing about CAC: no one knows what their true CAC is today. Given the trend toward enhancing user privacy, it’s very tricky to calculate how many users you acquired via paid vs organic channels (and how they overlap). Tracking multi-touch attribution is getting more challenging, and most customers are taking longer and multiple channels to consider a brand before they buy. You may get a cleanish view into your blended CAC (cost on upsell, expansion, and renewal efforts) and your sales, but estimating precise marketing costs for acquiring new users is very difficult today.

The main reason investors watch LTV is to track how much you can spend on marketing while still remaining profitable. That's pretty much it - to use as a benchmark to compare and contrast different marketing channels. Thus, if you don't segment it per marketing channel / campaign (and I have never seen it cleanly done, but prove me wrong), your lifetime value for a customer is useless.

I think I went through at least 5 different LTV calculations and approaches throughout my analytics journey (contractual, not contractual, including free trials, excluding trials, inverting retention, the Patrick’s way, etc). And none, I believe, represented a true user value. Given that CAC is a dark world filled with the unknown, I have seen many companies exclude it from their LTV and report it simply as user revenue multiplied by user lifetime. But that makes it a different metric that does not represent the actual value of a user anymore. I’m not even quite sure if it represents anything. Many SaaS businesses have multiple subscription tiers, and plans, so LTV becomes more of a passive metric that does not lead to any actual insight that you can act on.

And now imagine that (1) you have a very approximate CAC that can deviate 4x times either way (a true story), and then (2) a very questionable LTV that is (a) not sensitive to upgrades and downgrades, or worse - (b) excluding gross profit via promos, and refunds (and that % can be quite high), and now you have to try to explain to your dear investors why your LTV is not 3x higher than CAC. It becomes dangerous and flawed as executives tend to abuse LTV by using it as a baseline for revenue forecasting and then for planning budget spend based on its forecasted revenue.

Good luck estimating your Month To Recover CAC with all of that.

Churn

Why churn is challenging:

Churn is not a cancellation.

Involuntary churn data often are not easy to get.

Blended churn is misleading.

New and not up-for-renewal users have to be excluded from churn calculation.

I’ve written a lot about churn already. Monitoring it and cleanly reporting it is crucial for SaaS (unlike B2C where it can be less damaging). Surprisingly, many executives and VCs don’t quite get the concept of churn. They monitor it wrongfully by looking either at blended churn, or pulling new customers into the denominator, or equaling churn with cancellations. Read more - As The World Churns.

Overlooked KPIs

I should have called this section What the Board Should Be Looking At Instead, but frankly, they look at everything with a heavy focus on financials (and you can’t fool with balance and income statements like you’re able to with growth metrics). And yet some KPIs, especially the ones related to user behavior, are underrated and often overlooked, such as: DAU/MAU ratio, expansion customers, trial conversion rate, Day 7 retention, network score or referral score. To highlight a few:

DAU/MAU Ratio

Just because your customers pay you for the product, it doesn't necessarily mean they actually are using it in a way that you’d expect.

DAU/MAU Ratio shows what % of monthly customers use your product every single day.

You can use WAU/MAU or DAU/WAU ratio depending on the expected frequency of usage for your product. If you are not sure how to get that, read - User Engagement and Activity Histogram Analysis. Some SaaS products or services are expected to be used daily. Others are weekly or even monthly. So make sure you run that analysis first thing to know how to approach your metrics.

I haven’t met a business yet that would have strong financials with low customer usage. In my experience, frequent and strong engagement precedes and is an early indicator of future MRR growth (via re-subscriptions, resurrections or expansion revenue). A low DAU/MAU ratio is a predictor of Churn. This is the reason why at MyFitnessPal we pay a lot of attention to our product usage: the more often users log foods using our app, the more likely we will retain them and help them reach their goals.

Another reason why I like DAU/MAU ratio is that you can't fool with it or deviate. It's simple and yet very precise to reflect your actual engagement (unlike MAU which may include visitors, or retention that can be based on the app_open or received_notification events and not real user activity, or churn that might contain users-who-can't-churn in a denominator, making your rate look small or negative).

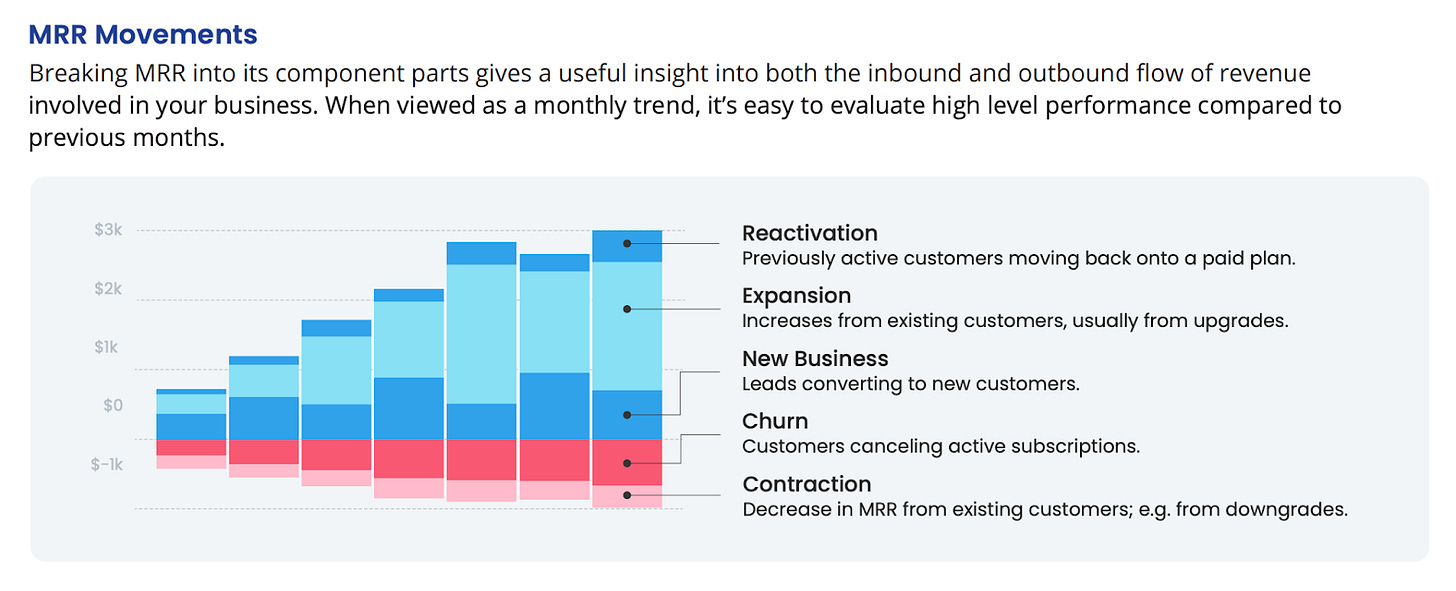

Expansion customers

I mean customers, not revenue here, as we usually break MRR on segments, but not customers. In a given month, for example, we segment recurring revenue on reactivation, expansion, new, churn, and contraction:

Revenue breakdown is important, but as you know, customers are not transactions. One customer doesn’t mean one payment. Even though expansion revenue is often small compared to total MRR and its segments (I think the benchmark is 30%), but % expansion customers can be quite large. One of the reasons for such discrepancy is that often businesses offer a discount to encourage users to upgrade. But the value of an upgraded user is different.

A few years ago I was in a meeting watching the Board argue about if switching from a monthly to an annual plan with a 50% discount should be considered an Upgrade or Downgrade. From one side, we were getting significantly lower annualized MRR from those users, so it should be regarded as a Downgrade. From another side, getting these users into annual subscriptions increased LTV, and given annual users are less likely to churn than monthly, it should be considered an Upgrade.

If your Northstar is LTV, you should treat these as expansion (upgraded) customers, even though they won’t be fully reflected in expansion revenue. If your goal is to maximize profit short term, you probably should treat them as contracted users.

Referrals and referees

This is relevant for products where users can bring in more (new or potential) customers by sharing, referring, affiliating, or else. I remember how we scaled Change.org from 50M to 250M active users by doing User Segmentation and Power User Analysis and monitoring the influence score (a very simple proxy to measure network effects) that represented the proportion of referred (we called them recruited) users for each Share action event.

Power user’s stats often are invisible for investors and are not requested or reported. In analytics, these “whales” mimic and reflect DAU/MAU rate and speak of your pool of opportunity for revenue expansion.

“Since Power Users are generally a small share of the user base, companies frequently overlook them. Unfortunately, this results in missing high-ROI opportunities to achieve revenue wins or unlock larger product improvements.” - from Reforge The Power User Trap.

Disclosure: after working with too many 360 customer view or data attribution and "campaign lifecycle data" platforms over the years, I gradually lost my trust in marketing growth (no offense to my fellow growth hackers). I have seen companies burning too much too fast to get too little traction, and CAC and LTVs data often didn't reach even a low acceptable bar to trust or act on it. From an analytics perspective, acquiring "external" data (generated or passed by ads platforms, social media, plugins) has always been and will continue to be a challenge which is likely to get worse with time.

Product analytics, on another hand, mostly utilizes "internal" user activity data that you can access, validate, cross check, and scale. And it's inspiring to watch companies grow by heavily developing their product and business strategy based on user activity and behavior analytics rather than optimizing paid marketing with last-click attribution.

Using the same data, analysts have the power to draw either a compelling story or make it look like a sinking ship. Playing with a user definition, activity, averages, and rates, we can tailor LTV to look higher than CAC, Churn to be negative, or ARPU to be high. Investing in analytics, due diligence, and tooling should secure clean reporting with high precision and trust.

Thanks for reading, everyone. Until next Wednesday!